Post Views: 7,165

ViewsTranscultural Analysis of Medical Device Alarm Trepidations: A Nursing Perspective and New Theory Proposal

By Colleen Lindell, RN, MHSA, CNOR, PhD in Medical Informatics

Introduction

“In 1994, Dr. Lucian L. Leape opened medicine’s Pandora’s Box in his 1994 JAMA paper, “Error in Medicine.” He said he was well aware that medical errors were not being reported. A study conducted in two obstetrical units in the UK found that only about one-quarter of adverse incidents were ever reported, to protect staff, preserve reputations, or for fear of reprisals, including lawsuits. An analysis found that only 1.5% of all adverse events result in an incident report, and only 6% of adverse drug events are identified properly. If hospitals admitted to the actual number of errors for which they are responsible, which is about 20 times what is reported, they would come under intense scrutiny (Null).”

The under-reporting of medical errors is no surprise to most caregivers. Caregivers want employment security, fear legal complications and contemplate that most medical errors do not cause patient injury or death. Let’s consider those medical errors that have caused patient injury or death. While the number is considered underreported, the impact to the patient’s family and ethical, social and legal implications can be immense.

Medical devices are used for the purpose of diagnosing, monitoring, treating, or to alleviate disease in order to support or sustain life. It is not out of the ordinary for a patient to have several medical devices attached to them or in their hospital room. Medical device alarm system errors are a contributing factor to the medical errors analysis reported by Dr. Leape. A 2006 American Journal of Medicine study found that 99.4% of medical device alarms were determined to be false (Atzema 2006). This is a dangerous situation for patients, as caregivers will tend to ignore medical device alarms when they are consistently false.

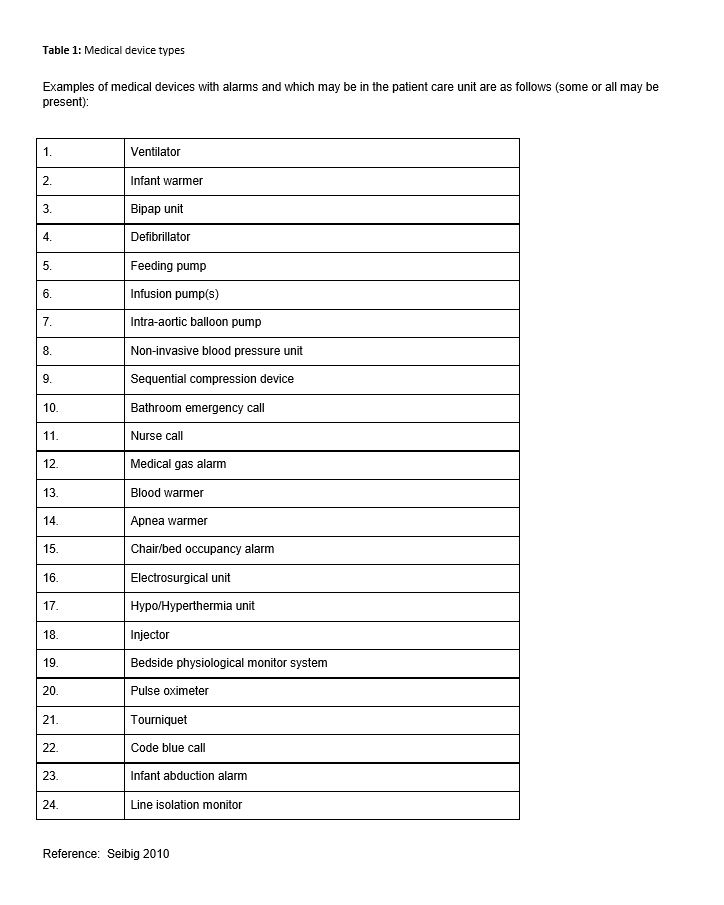

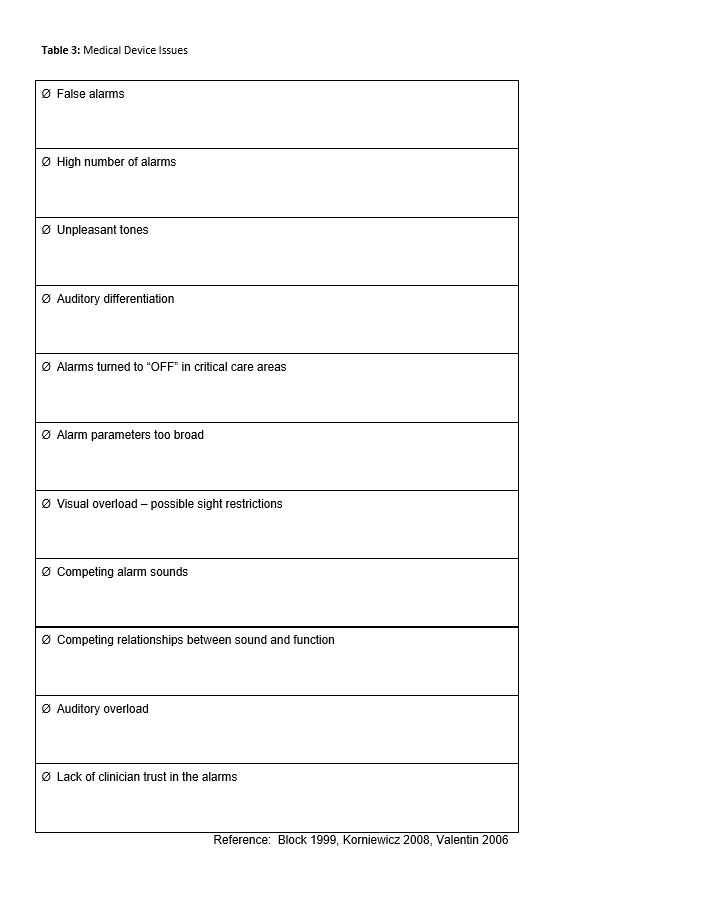

Patients are at risk when alarm conditions aren’t effectively communicated. We discern that medical device alarms are often numerous, in competition with each other, many alarm notifications are false, cause auditory overload, lack differentiation, are often turned to “off” (leading to no communication of the alarm condition), the default alarm parameters may be too broad or narrow for some patients, and there can be visual overload in addition to possible sight restrictions due to placement or location of the medical device (Cvach 2012). Table 1 describes the numerous medical devices that may be present on or in a patient’s room.

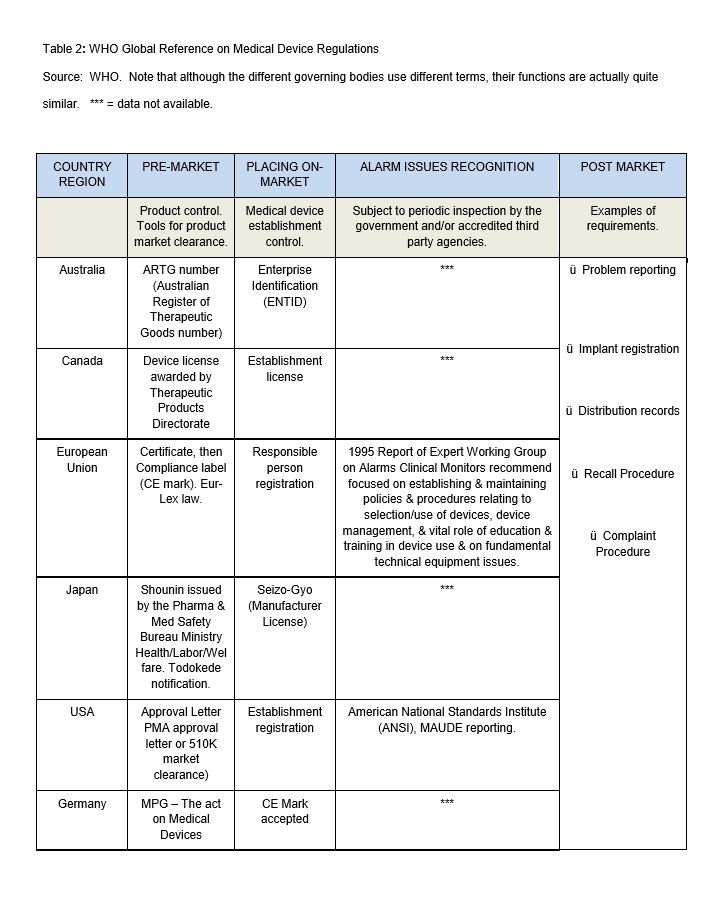

Mandatory problem reporting requires that serious problems are reported and relayed to other users for preventive purposes. However, there seems to be a concern among users that the information provided for medical device problem reporting may become a personal legal liability, especially if it turns out the problem was actually caused by incorrect use of the device. This means there is a general reluctance to report problems associated with the use of medical devices, even where such reporting is mandatory by law (e.g. in the United States and some countries in Europe). Regulatory authorities both in Europe and North America are experiencing a lack of reporting cooperation from device users. Even though is a highly regulated industry , there are differences between countries, particularly as it relates to alarm issues recognition and post market surveillance (Table 2).

End-user complaints are an early indication of potential problems and should not be ignored. Proper complaint investigation may lead to the discovery of more serious problems (WHO, ECRI). Manufacturers of medical devices may or may not be aware of their device problems, even though most have a local, regional or international presence, and engage in the product development life cycle process (with regulatory oversight).

In 2002 The Joint Commission (TJC) released a Sentinel Event Alert that exposed medical device alarm malfunctions and use error as a significant root cause of ventilator-related deaths and injuries. It also established a national patient safety goal to improve the effectiveness of clinical alarms (TJC 2002). Clinical alarms warn caregivers of hazards and can be instrumental in preventing patient injury or death.

On April 10, 2013, TJC issued another Sentinel Event Alert related to medical device alarm safety that warned hospitals against alarm fatigue caused by medical devices. TJC stated that 85-99% of alarms do not require clinical intervention. Consequently, caregivers become overwhelmed, desensitized, and endure alarm fatigue. If the caregiver turns off the alarm, turns the volume down or changes the default parameters, patient safety is compromised. TJC also reported on 100 alarm-related events occurring between January 2009 and June 2012 with 80 of those resulting in death, 13 in permanent loss of function, and 5 requiring unexpected, additional care.

Consequently, the TJC will be re-issuing the National Patient Safety Clinical Alarms Standards in 2014, requiring hospitals to identify the most important alarm signals to manage and in 2015 will require the establishment of policies and procedures for managing the most important alarms. Alarm issues are among the problems most frequently reported to the ECRI .

The ECRI Institute is a non-profit organization that has been in existence for over forty years. ECRI has a long history of investigating clinical alarm problems, recommending solutions and is designated as an Evidence-Based Practice Center by the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and is listed as a federal Patient Safety Organization by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Currently, ECRI recommends that medical device alarms be safe, logical and consistent with facility practice, thus encouraging hospitals to conduct an internal assessment and implement actions in response to their findings, with special consideration for personnel, procedures, equipment and local practice. Despite their long-standing recommendations, alarm hazards have continued to be listed on their top ten technology hazards annual publication for the past six years (ECRI 2008-2013).

The Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation (AAMI) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1967. AAMI is the primary resource for the industry, the professions, and the government for national and international standards. AAMI also administers a number of international technical committees, such as the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electro technical Commission (IEC), and the U.S. Technical Advisory Groups (TAGs). They publish requirements such HE48, which distinguishes alarm characteristics, decibel volumes, silencing capabilities, notification, user testing requirements for audible signals, angle and distance readability, visual alarm flash rates, various and specific color flashing for priority alarms, audible signals, frequency, pitch and timeframes for the retention of alarm limits if power is lost.

The World Health Organization (WHO, Geneva) publication “Medical Device Regulations: Global overview and guiding principles “provides guidance to Member States (Australia, Canada, European Union, Japan, US) wishing to create or modify their own regulatory systems for medical devices. Appendix B provides information specific to the history of medical device regulation, specifically related to regulation and surveillance. Membership to WHO is national and international (Appendix A). Although there are many organization memberships worldwide related to medical devices, there is a lack of publications addressing transcultural medical device alarm “systems ” issues and their safety impact on patients and caregivers. Transcultural medical device use is thought to be consistent cross-county [s13] due to the global nature of medical device manufacturers and their supply chain; however, a transcultural analysis of the published database and medical literature hasn’t been undertaken.

From a nursing perspective, there are several theories applicable to nursing practice in a healthcare environment where nursing seeks to support universal compliance, healing and wellness (Leininger). The first applicable theory is that of duty, where there is an obligation to act as patient advocate and to “do no harm.” This is not based simply on a negative duty of non-maleficence but also on a positive duty of beneficence whereas we seek to do good by providing a social good, with certain rules of conduct, and a social accountability or responsibility to provide care (V. Sharpe). Madeleine Leininger’s theory is based on a study of cultures which sought to understand similarities (culture-universal) and differences (culture-specific) across human groups (Leininger, 1991). This theory takes into account the people, environment (culture), nursing and health as integral components of transcultural nursing. As a transcultural model, it is universally adaptable to nursing practice.

This review was exploratory and sought to identify medical device alarm issue commonalities from a country and categorical medical device alarm system issues by reviewing published literature, and categorizing it against established ECRI criteria. Following this review, consideration was given to the application of a new nursing theory entitled, “Medical device interaction theory”. This theory is specific to nursing, as nursing is the only profession that cares for patients continually, without interruption.

Further, this new theory seeks to support medical device alarms as a system rather than as individual medical devices permitting manufacturers, clinicians, and human factors experts to work as a team in their development, interaction, and integration. The theory constructs are adapted from the ECRI noted categories of People, Equipment, Policy and Procedure, and Local Procedure. This review will support and address the following questions:

– To what degree do cross-cultural variations of medical device alarm systems exist?

– How can specific intra-country variations be identified?

– What transcultural commonalities clarify the understanding of medical device alarm issues?

– How can a new nursing theory contribute to future research investigating medical device alarm issues?

Medical device alarm conditions must be quickly and consistently conveyed. A critical clinical alarm is any audible or visual indication from a system or device that, when activated, may result in injury or death unless immediate clinical intervention results. Thus, particularly with critical clinical alarms, if the alarm indications aren’t effectively communicated, patients are at risk. Medical device alarms also warn caregivers of hazards and can be instrumental in preventing patient injury or death; however, there are many issues associated with clinical alarm systems (Block 1999, Korniewicz 2008, Valentin 2006). A collation of medical device issues is presented in Table 3. The published literature identifies numerous issues with medical device alarming which can be populated into four categories recommended by ECRI. They are as follows:

- Personnel – clinician trust, confusion, staff assignment, staffing model, shift change, role clarity, back up procedures. Lack of intelligent and predictive medical device alarm systems has led to nurse distrust, silencing, disabling or turning off of medical device alarming system(s), and expectations vs. actual may differ. Misuse of medical device equipment by the end-user (e.g. disabling the safety features) is clinician specific.

- Equipment – Reliability, lack of differentiation between devices, priority confusion, effective exchange of information, sensitivity and specificity, and integrated systems issues (software, network, wireless, etc.).

- Policy and Procedure – specific to medical device and their alarms may or may not address alarm limits, alarm priorities, default settings, adjusting alarm settings, silencing, notification, response (primary, secondary, and tertiary), disabling, standardization, downtime, and assignment, accountability for alarm response, adverse event documentation and review.

- Local Procedure – such as device maintenance, alarm sitters, remote alarm monitoring, reporting systems, education or training programs, and real-time temporary changes to alarm settings.

The above four categories have patient care impact, affect how medical devices are managed and directly impact the workflow of the unit. There can be a great deal of variation between caregivers, patient environments, local and individual practice. Caregivers are responsible for the communication and coordination of patient care, and subsequently, their communications and work patterns are reflective of the patient care unit workflow design (Cain).

End-users are caregivers with qualifications and training in the proper use of the device, and should be familiar with the indications, contra-indications and operating procedures recommended by the manufacturer. When using medical devices, users should always bear in mind that the safety and health of the patients are in their hands. The user has the responsibility to employ the medical device only for the intended indications (or to assure that any non-indicated use of the medical device does not compromise the safety of the patient and other users). The end-users’ experience is based on usability.

Usability can be defined as how well users learn and use a product to achieve their goal as well as how satisfied they are with that process (http://www.usability.gov/basics/index.html ). Current alarm systems demonstrate usability concerns primarily related to clinician’s reduced trust, low efficiency, and lack of auditory and visual differentiation of the indication, priority level confusion, and ineffective notifications (Korniewicz 2008). Barton (2011), in her review of clinical decision support (CDS) systems, comments on information alerts such as interaction alerts and patient reminders stating that they “contribute to alert fatigue” and recommends that more “pertinent” alerts be provided to staff if an action is required (Sendelbach). Further, she recommends educating nurses on the knowledge of human factors principles considered important in the design and implementation of effective clinical decision support alerts. This includes medical device alarms.

It is important to know that with the implementation of current and future CDS systems, there will be additional noise, color and messaging, placing a further toll on practicing caregivers, already weary by the quantity of alerts and alarms (Phansalkar 2010). The impacts of alarms on patients have been recently studied and include: sleep disturbances, increased heart rate and blood pressure, slow healing and recovery, and increased length of stay. Furthermore, impact on the caregiver has recently been studied and includes: increased occupational stress, decreased work performance, delayed recognition of alarms and increased errors (Choiniere 2010, Hsu 2012).

Methodology

Step One. Utilizing the WHO database, a review of globally regulated medical devices baseline country information was performed to analyze the medical device regulatory and post-market environment from a global country perspective and to review medical device between-country, alarm-related documented issues. This data was obtained and categorized by country, pre-market controls, establishment controls, inspections and post-market surveillance (Table 2).

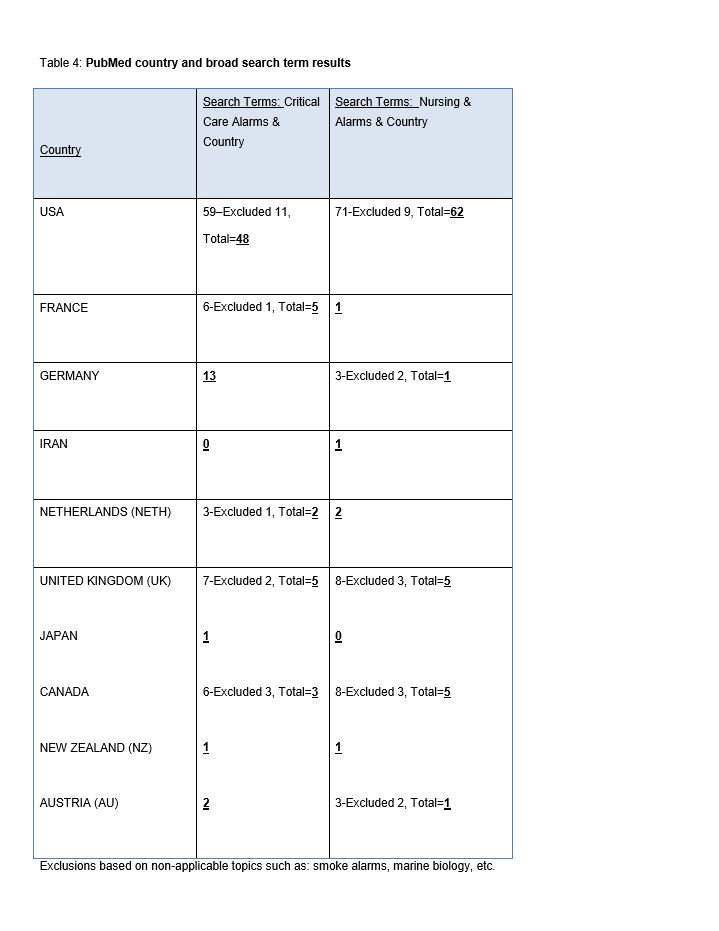

Step Two. A PubMed database search was performed using broad search terms: “Critical care alarms and [country]” for USA, France, Germany, Iran, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, New Zealand, Austria, and Hungary. “Nursing and Alarms and [country]” for USA, France, Germany, Iran, Netherlands, United Kingdom, Japan, Canada, New Zealand, Austria, and Hungary (Table 4).

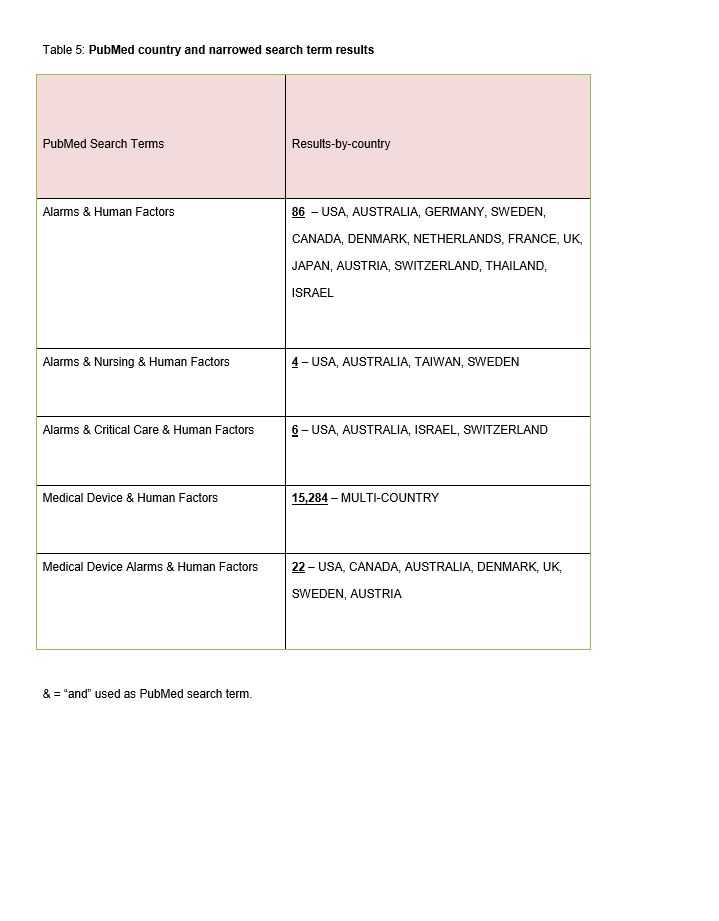

Step Three. A PubMed database search was performed using narrowed search terms: “Alarms and human factors, Alarms and Nursing and human factors, Alarms and Critical Care and human factors, Medical device and human factors, Medical device alarms and human factors” (Table 5).

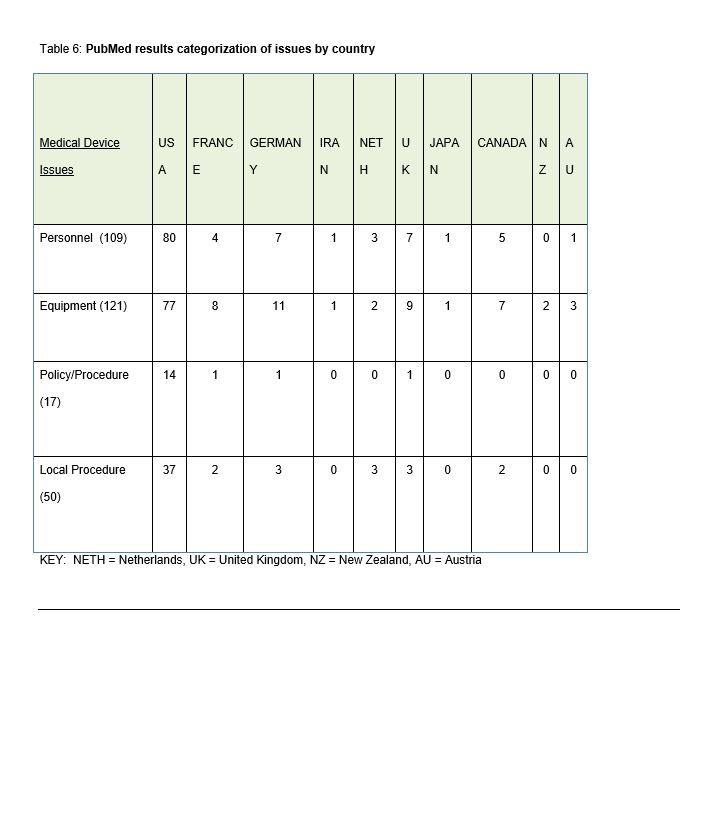

Step Four. The results were reviewed, analyzed and collated using the ECRI Framework of Medical Device Issues categorized using the ECRI recommendations: personnel, equipment, policy and procedure and local procedure. The results were recorded by country (Table 6).

Step Five. The results were synthesized, and opportunities for improvement identified. Consideration was given to application of a new nursing theory.

Results

As the main purpose of this review was to review and understand transcultural medical device alarm system issues, let’s begin with the WHO baseline country examination (Table 2), which provided global information specific to health technologies, particularly on the availability of specific medical devices, policies, guidelines, medical device regulations, controls, standards and services. The following countries are considered by WHO to have the most advanced medical device regulations (MDR): Australia, Brazil, Canada, EU, Japan, USA and Germany . This is not evident in the table, as there is missing information for Australia, Canada, Japan and Germany.

Evident is that although the differing countries use different terms (e.g. pre-market and placing on market), their functions are actually quite similar. The pre-market approval requires some type of certificate, letter or notification and placing a medical device on-market requires some type of licensure, registration, identification or CE mark. The differences begin to emerge as ambiguous or as “data unavailable” (Australia, Canada, Japan and Germany) when reviewing the “alarm issues recognition” and post market requirements for problem reporting, product registration, distribution, recall procedure and complaint procedure. In the USA, there is the MAUDE adverse event database, which houses medical device reports of suspected device-associated deaths, serious injuries and malfunctions submitted to the FDA by mandatory reporters (manufacturers, importers and device user facilities) and voluntary reporters such as health care professionals, patients and consumers.

(http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cdrh/cfdocs/cfmaude/search.cfm ). The only other country that reported on alarm issues recognition is the European Union : “Expert Working Group on Alarms on Clinical Monitors ” which had a report dated 1995; no updates could be located via the WHO database or their associated hyperlinks.

The PubMed broad search terms review (Table 4) revealed that the majority of publications related to “country and nursing, critical care alarms or alarms” are printed in American journals (n=110). The next highest country was Germany with 14 publications, and the remaining countries had at least one article. The PubMed narrowed search terms review of publications (Table 5) related to “[country] and alarms, human factors, nursing, critical care, medical device, or medical device alarms” revealed over 15,284 multi-country publications for “medical device and human factors”. This subset of publications was not reviewed and was noted for assessment purposes only. This was followed by 86 multi-country (USA, Australia, Germany, Sweden, Canada, Denmark, Netherlands, France, UK, Japan, Austria, Switzerland, Thailand, Israel) publications for alarms and human factors, followed by 22 multi-country publications (USA, Canada, Australia, Denmark, UK, Sweden, Austria) related to medical device alarms and human factors. Finally, there were 10 multi-country (USA, Australia, Taiwan, Sweden, Israel, Switzerland) publications related to “alarms, nursing, human factors, or critical care”.

A total of 271 publications (broad plus narrowed results) were reviewed for causation references related to medical device issues and were populated using the four ECRI recommended categories: personnel, equipment, policy/procedure or local procedure (Table 6). Some publications reported more than one issue and therefore were recorded as multiples. The results are listed below in numerical order of findings:

- Equipment (n=121) – Reliability, lack of differentiation between devices, priority confusion, effective exchange of information, sensitivity and specificity, and integrated systems issues (software, network, wireless, etc.).

- Personnel (n=109) – Clinician trust, confusion, staff assignment, staffing model, shift change, role clarity, back up procedures. Lack of intelligent and predictive medical device alarm systems has led to nurse distrust, silencing, disabling or turning off of medical device alarming system(s), and expectations vs. actual may differ. Misuse of medical device equipment by the end-user (e.g. disabling the safety features) is clinician specific.

- Local Procedure (n=50) – such as device maintenance, alarm sitters, remote alarm monitoring, reporting systems, education or training programs, and real-time temporary changes to alarm settings.

- Policy and Procedure (n=17) – specific to medical device and their alarms may or may not address alarm limits, alarm priorities, default settings, adjusting alarm settings, silencing, notification, response (primary, secondary, and tertiary), disabling, standardization, downtime, and assignment, accountability for alarm response, adverse event documentation and review.

Discussion

While the study is simple and easily replicated, there are inherent limitations regarding this type of research. The limitations to this type of research are as follows:

- It is a retrospective review and analysis.

- Medical device alarm issues are under-reported.

- There are between country clinical practice pattern and local procedure variations not identified in this research.

- Manufacturer variations and regulation differences may account for the findings.

- Outside of the USA, country reporting systems for medical device adverse events are difficult to identify or non-existent.

In addressing the questions posed at the beginning of this paper, we now answer them in light of the results attained:

- To what degree do cross-cultural variations of medical device alarm systems exist?

- How can specific intra-country variations be identified?

- What transcultural commonalities clarify the understanding of medical device alarm issues?

- How can a new nursing theory contribute to future research investigating medical device alarm issues?

It was difficult to identify between country use variations due to the known under-reporting and low number of publications outside of the USA; however, we know that caregiving practice is similar as patients , patient diagnoses and monitoring is universal, and this is further demonstrated by the transcultural distribution of medical devices across the world, as well as the universal applicability of medical and nursing textbooks. Therefore, we can try to extrapolate based on the multi-country publications which demonstrate that medical device issues are primarily equipment-related (unreliable, lack differentiation, priority confusion, poor sensitivity and specificity, and inadequate system integration). Secondarily, personnel issues such as lack of trust, device confusion, staffing, and use errors, as well as misuse of medical devices, is a universal practice. Thirdly, local procedures for device maintenance, monitoring of alarms, training and education programs are inadequate. Lastly, policies and procedures lack specificity related to device use in areas such as setting limits, defaults, adjustment, lack of standardization, and failure to identify, report and review medical device related alarm incidents.

Medical device alarm issues have been ongoing since the beginning of their use and continue to be problematic. This is a patient safety issue that clearly needs to be better understood. These research findings confirm that the issues are transcultural and that the issues can be categorized using the ECRI groupings of People, Equipment, Policy and Procedure, and Local Procedure. Noticeably, the primary areas for improvement are personnel and equipment. This is no surprise due to the fact that the majority of the alarms are false positive leading to clinician mistrust and misuse. While there are few publications pointing to policy and procedure, this issue was raised in several multi-national publications. Could this is be a larger issue possibly strengthening the argument that due to a lack of policy and procedure (responsibilities, roles, maintenance, etc.) most of the issues can be mapped out to people and equipment?

The WHO database is considered a transnational country database; however, it lacks specific information related to medical alarm system issues recognition and post market requirements. As concerns are transcultural, there is room for improvement, specifically in this global database on alarm issues and surveillance (Table 2). With the current electronic integration of databases and systems, it would seem possible that country information could be identified, collated and populated in this type of global database, for the good of all members. The concept of a global safety and surveillance program may be difficult to implement, however the benefits of this type of program should be considered. Global recall procedures would be easier to implement, complaint procedures and early identification of medical device problems with “triggers” put into place to promptly notify. Distribution records would be easier to maintain and coordinate cross county.

It is critical that medical device manufacturers set minimum technical safety standards and that these have universal applicability such that they can be understood by all and are user friendly. Under-reporting is inherent with medical device alarm issues given the high number of alarm reported issues. They are commonplace and have become accepted in the healthcare environment even though we know they are dangerous. Future alarms will likely have a goal of 100% sensitivity and 100% specificity with unobtrusive yet informative sounds (Arney 2009). Alarm enhancement systems (pagers, mobile phones, nurse call systems, wireless communication devices) provide a means to communicate alerts and alarms to caregivers, yet there will always be a need to silence them, especially within an integrated monitor. Silencing an alarm, however, shouldn’t mean the alarm fails to get appropriately prioritized and communicated to the right person.

The final research question posed was related to theory: Might there be a new nursing theory applicable to medical device alarm issues? This article proposed a new theory for medical device alarm issues consideration, the “Medical Device Interaction Theory”. Due to the increasing number of alarming devices being placed on patients and the integration of these systems as one means to adapt, it is important that we fully understand how these devices interact and their effects on patients and caregivers. Chambrin (1999), observed one false alarm every thirty-seven minutes in an intensive care setting and an American Journal of Medicine study in 2006 found that 99.4% of alarms were determined to be false (Atzema 2006). False positive alarms occur when the system sounds an alarm and no real fault is present, such as when the patient is at rest and the heart rate decreases and the alarm sounds (the lower threshold exceeded). Another example of a false alarm results from an awkward intravenous line placement (e.g. an intravenous line placed in the bend of the wrist or elbow), which causes a frequent downstream occlusion with patient movement, yet is quickly and independently resolved when the bend is no longer present.

A high number of false alarms lead to the disabling of notification alerts and alarms as well as detracting from patient care. A false negative alarm occurs when the patient has a problem, yet the condition goes undetected by the monitor and no alarm is sounded. False alarms consist of both false negative and false positive alarms, and when prevalent, quickly lead to clinician mistrust. This undetected condition could be related to clinician deactivation of the alarm or when there is failure to alarm when a condition meets alarm criteria. While these situations are difficult to detect, they provide the greatest situational hazard for patients. Sensitivity and specificity studies with individual devices and with integrated devices will help to better understand and correctly identify false alarms. False alarms occur when the mode of alarm generation is the source of many false alarms without clinical relevance.

From a human factors perspective, the medical device alarm system design needs improved differentiation (audible, visual, color, messaging), as well as developed system integration allowing for decreased priority confusion between systems and increases sensitivity and specificity with advanced system integration. This will be difficult as manufacturers are reluctant to open source their software and consideration must be given to costs. Medical device alarm systems have the potential to prevent errors, injury or death; however, they demonstrate “usability” concerns primarily related to clinician reduced trust, low efficiency, lack of auditory/visual differentiation, priority level confusion and ineffective notifications.

The Medical Device Interaction theory seeks to support medical device alarms as a system rather than as individual medical devices, permitting manufacturers, clinicians, and human factors experts to work as a team in their development and integration. The constructs of People, Equipment, Policy and Procedure, and Local Procedure should be further studied and research undertaken to develop specific measures for these categories such that this information can be applied towards improvements to practice, research, education and theory.

Figure 1: Medical Device Interaction Theory

Following a review of these databases, we offer direction for future research, focusing on medical device manufacturers, human factors, administration, end-user collaboration, and theory development.

See more below for References and Appendix

[read more=”Read more” less=”Read less”]

References

ACCE Healthcare Technology Foundation 2006. White paper: Impact of Clinical Alarms on Patient Safety. http://thehtf.org/White%20Paper.pdf <Accessed November 13, 2010>

Arney D., Fischmeister S., Goldman JM., Lee I., Trausmuth R. Plug-n-Play for Medical Devices: Experiences from a Case Study. Biomedical Instrumentation and Technology. July/August 2009. V 23, No. 4, pp.313-317.

Atzema C., Schell M.J., Borgundvaag B. et al. ALARMED: adverse events in low-risk patients with chest pain receiving continuous ECG monitoring in the Emergency Department. A pilot study. Am J Emerg Med. 2006 Jan;24(1):: 62-7.

Barton A.J. Information Technology and the Clinical Nurse Specialist. Clinical Nurse Specialist September/October 2011.

Benson Tim. Principles of Health Interoperability HL7 and SNOWMED. Springer – Verlag London Limited 2010. ISBN 978-1-84882-803-2

Block F., Nuutinen L., Ballast B. Optimization for alarms: a study on alarm limits, alarm sounds, and false alarms intended to reduce annoyance. Journal of Clinical Monitoring and Computing 15:75-83, 1999.

Cain C.H., Haque S. Patient Safety and Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook for Nurses: Vol. 2

Chambrin M. Alarms in the ICU: how can the number of false alarms be reduced? Critical Care Aug 2001 V5 N4.

Chambrin M., Ravaux P., Calvelo-Aros D., Jaborska A., Chopin C. Boniface B. Multi-centric study of monitoring alarms in the adult ICU: a descriptive analysis. Intensive Care Med 1999:25:1360-1366.

Choiniere D. The Effects of Hospital Noise. Nursing Admin Quarterly 2010; 34 (4): 327-33.

Cvach M. Monitor Alarm Fatigue: An Integrative Review. Biomedical Instrumentation & Technology July/August 2012.

ECRI Institute Issues “Top ten health technology issues for 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013” https://www.ecri.org/

HIMSS Interoperability Definition and Background. April 24, 2012. http://www.healthcareitnews.com/directory/interoperability <Accessed March 3rd, 2013>.

Hsu T. et al. Noise Pollution in Hospitals: Impact on Patients. Journal of Clinical Outcomes Manage 2012; 19 (7): 301-9.

International Medical Device Regulators Forum http://www.imdrf.org/ghtf/ghtf-archives.asp <Accessed November 16, 2013>.

ISO 14971:2007, Medical devices – Application of risk management to medical devices, or the regulatory Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF).

Korniewicz D., Clark Tl, David Y. A national online survey on the effectiveness of clinical alarms. American Journal of Critical Care. 2008;17: 36-41.

Leininger M. Transcultural nursing: Concepts, theories, research, and practice. Columbus, OH: McGraw-Hill College Custom Series; 1995

Null G. Death by Medicine. http://www.whale.to/a/null9.html < Accessed November 18, 2013>.

Phansalkar S. Edworthy J., Hellier E., Seger D.L., Schedlbauer A., Avery A.J., Bates D.W. A review of human factors principles for the design and implementation of medication safety alerts in clinical information systems. Journal American Medical Informatics Association 2010;17:493-501.

Randeo Si. Harmonization of Regulation in India: Benefits and challenges of Harmonization. 13th AHWP-FICCI Workshop. New Delhi, India: 2008.

Sendelbach S. Alarm Fatigue. Nurs Clin N America 47(2012) 375-382.

Sharpe VA. Why do no harm? Theor Med. 1997 Mar-Jun;18(1-2):197-215.

Siebig S. Kuhls S., Imhoff M, Gather U., Scholmerich J., Wrede C. Intensive care unit alarms – how many do we need? Critical Care Medicine 2010 Vol.38, No.2.

The Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert – Preventing ventilator-related deaths and injuries. Issue 25, February 2, 2002 http://www.jointcommission.org/sentinel_event_alert_issue_25_preventing_ventilator-related_deaths_and_injuries /<Accessed March 2nd, 2013>.

US National Library of Medicine Fact Sheet http://www.nlm.nih.gov/pubs/factsheets/dif_med_pub.html <accessed October 30, 2013>.

World Health Organization Medical device regulations: global overview and guiding principles. 1. Equipment and supplies – legislation 2.Equipment and supplies – standards 3.Policy making 4.Risk management 5.Quality control I. Title. ISBN 9241546182.

Valentin, A. Capuzzo M., Guidet B., Moreno R., Doanski L, Bauer P. Metnitz P. Patient safety in intensive care: results from the multinational sentinel events evaluation SEE study. Intensive Critical Care Med 2006:32:1591-1598.

Appendix A: WHO country survey baseline data for regulated medical devices

Australia – Medical Device Problems and Adverse Events Therapeutic Goods Administration http://www.tga.gov.au/safety/problem-device-iris.htm

Brazil http://portal.saude.gov.br/portal/saude/profissional/default.cfm

France http://www.sante.gouv.fr/

Germany http://www.bmg.bund.de/

Health Canada http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/pubs/md-im/index-eng.php

Health Facilities Scotland http://www.hfs.scot.nhs.uk/online-services/incident-reporting-and-investigation-centre-iric/how-to-report-adverse-incidents/

Iraq http://www.kimadia-iraq.com/site/

Japan Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare http://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/policy/health-medical/pharmaceuticals/index.html

Netherlands http://www.rijksoverheid.nl/ministeries/vws#ref-minvws

New Zealand http://www.medsafe.govt.nz/

New Zealand Pharmacovigilence Center https://nzphvc-01.otago.ac.nz/carm-adr/carm.php

Northern Ireland Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety http://www.dhsspsni.gov.uk/index/hea/niaic/niaic_reporting_incidents.htm

United Kingdom – MHRA is a centre of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency http://www.mhra.gov.uk/Devicesindustry/Vigilanceandadverseeventreporting/index.htm

USFDA Medical Devices http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/Overview/default.htm

Wales Healthcare Excellence http://www.wales.nhs.uk/sites3/page.cfm?orgid=465&pid=56203

WHO Baseline Country Survey on Medical Devices, 2010. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2011/WHO_HSS_EHT_DIM_11.01_eng.pdf <Accessed November 16, 2013>.

WHO Medical Devices Regulations. http://www.who.int/medical_devices/safety/en/ <Accessed November 18, 2013>.

Appendix B: Medical Device Regulations Historical Review

Since the beginning of 1980s, the regulatory world for medical devices has changed dramatically. Initially, there were few countries that implemented and enforced medical device regulations. Currently, there are sixty to sixty-five countries that have implemented regulation for medical devices or will soon implement the regulation for medical devices (Randeo).

In 1992, the International Global Harmonization Task Force (GHTF) had five founding members (European Union, United States, Canada, Australia and Japan) and worked collaboratively with a mission to harmonize the implementation of Medical Device Regulation across the globe and with a goal to achieve greater uniformity between national medical devices regulatory systems (enhance patient safety and increase access to safe and effective medical technologies around the world).

In 2011, a voluntary group of regulators formed to build upon the work of GHTF and called themselves the International Medical Device Regulation Forum (http://www.imdrf.lorg). Today, the GHTF no longer exists and has been replaced by the IMDRF, which includes the same GHTF membership (European Union, United States, Canada, Australia, and Japan) and Brazil.

Today, the World Health Organization (WHO) is the Director, Coordinator and Authority for health within the United Nations system. The WHO has a mandate to encourage member countries to draw up national or regional guidelines for good manufacturing and regulatory practices, to establish surveillance systems and other measures to ensure the quality, safety and efficacy of medical devices and, where appropriate, to participate in international harmonization (WHO).

Post-market surveillance is a broad term that covers all monitoring activities of medical devices in use. The two major activities within surveillance are “post-market surveillance studies” and “adverse event reporting”. In post-market surveillance studies, specific and structured data collections are required of the manufacturer in one of two situations: (1) as a condition of product approval, or (2) to re-affirm product safety when post-market adverse event reports suggest that premarket safety claims are inconsistent with actual use and result in unacceptable risk. Japanese authorities and the FDA actively make use of surveillance data collection to augment the findings of pre-market trials. Adverse event reporting requires the registration and investigation of adverse events relating to the use of a device, and the authority necessary to oblige the manufacturer to recall or modify a defective device. All founding members of the GHTF have mandatory requirements for vendors or manufacturers to report all device-related events that have resulted, or could result, in serious injury or death. In some countries, mandatory adverse event reporting is also extended to users.

Table 1: Medical device types

Examples of medical devices with alarms and which may be in the patient care unit are as follows (some or all may be present):

Table 2: WHO Global Reference on Medical Device Regulations

Table 3: Medical Device Issues

Table 4: PubMed Country and Broad Search Term Results

Table 5: PubMed Country and Narrowed Search Term Results

Table 6: PubMed Results Categorization of Issues by Country

KEY: NETH = Netherlands, UK = United Kingdom, NZ = New Zealand, AU = Austria

[/read]

732 comments on Transcultural Analysis of Medical Device Alarm Trepidations: A Nursing Perspective and New Theory Proposal

Leave a Reply

Transcultural Analysis of Medical Device Alarm Trepidations: A Nursing Perspective and New Theory Proposal

By Nurse Advisor Magazine (Official)

“In 1994, Dr. Lucian L. Leape opened medicine’s Pandora’s Box in his 1994 JAMA paper, “Error in Medicine.” He said he was well aware that medical errors were not being reported.

My ex-husband and I had always managed to stay friendly after our divorce in February 2017. But I always wanted to get back together with him, All it took was a visit to this spell casters website last December, because my dream was to start a new year with my husband, and live happily with him.. This spell caster requested a specific love spell for me and my husband, and I accepted it. And this powerful spell caster began to work his magic. And 48 hours after this spell caster worked for me, my husband called me back for us to be together again, and he was remorseful for all his wrong deeds. My spell is working because guess what: My “husband” is back and we are making preparations on how to go to court and withdraw our divorce papers ASAP. This is nothing short of a miracle. Thank you Dr Emu for your powerful spells. Words are not enough.

Email emutemple@gmail.com

Phone/WhatsApp +2347012841542.

I’m a professional in all kinds of hacking services, which leads me into giving out a blank ATM card to all individuals & serious minded people only, We have help so many people and make them rich, this is real and guarantee sure our Atm will be attached to any serious buyer.

HERE IS OUR PRICE LISTS FOR THE CARDS

1,000 USD daily for 2 weeks cost 300 USD

1,000 USD daily for 1 month cost 500 USD

1,000 USD daily for 2 months cost 800 USD

1,000 USD daily for 3 months cost 1,000 USD

1,000 USD daily for 6 months cost 1,600 USD

1,000 USD daily for 1 year cost 2,700 USD

1,000 USD daily for 2 Years cost 4,800 USD

1,000 USD daily for 3 Years cost 8,900 USD

Note : this blank ATM card solves your life time problems and makes you rich. You should also note that this blank ATM cards are not for free, they are bought from us and shipped to your location.

We deal with serious people who want this Card.

Email : darkwebonlinehackers@gmail.com

WhatsApp: +1 (803) 392-1735

Be careful of people asking for your money or investment platforms promising huge returns. I saw an opportunity to invest in cryptocurrency about a month ago and I took my chance. I contacted a broker who I saw videos on You Tube and I invested a huge sum of money around £475,211 which was deposited using Bitcoin. They locked my account and requested more money before I could access it, and that was how I realized I was being conned. I saw a post on Quora about GEO COORDINATES HACKER With a little faith in me, I contacted them immediately, and discussed my situation, and sent all the information I had. In less than 48 hours I was able to recover my Bitcoin. I wish to recommend them to everyone out there. They are capable of recovering any crypto coins Bitcoin. I’m so happy to share this excellent news with you all. Contact them if you need any crypto recovery assistance, through Email: (geovcoordinateshacker@proton.me)

Email; (geovcoordinateshacker@gmail.com)

Website; https://geovcoordinateshac.wixsite.com/geo-coordinates-hack

I lost my job few months back and there was no way to get income for my family, things was so tough and I couldn’t get anything for my children, not until a met a recommendation on a page writing how Mr Bernie Doran helped a lady in getting a huge amount of profit every 6 working days on trading with his management on the cryptocurrency Market, to be honest I was skeptical at first but I took the risk to take a loan, and I contacted him unbelievable and I was so happy I received a profit of $15,500 with an investment of $1500 within 7 days of trading , the most joy is that I can now take care of my family, i am just sharing my testimony on here. I don’t know how to appreciate your good work Mr. Bernie Doran, God will continue to bless you for being a life saver I have no way to appreciate you than to tell people about your good services. He can also help you recover your lost funds, For a perfect investment and good return on investment contact Mr Bernie Doran on Gmail : Berniedoransignals@gmail.com his telegram : IEBINARYFX or his whatsApp : 1 ( 424 ) 285 – 0682